City | by Sebastian Eick

August 03, 2023

Two Takes on Creative Urbanism

and Whatever Happened Between Them

By: Moozhan Shakeri

City | by Sebastian Eick

August 03, 2023

and Whatever Happened Between Them

By: Moozhan Shakeri

![]() This blog is part of a project that received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie SkłodowskaCurie grant agreement No. 101068688.

This blog is part of a project that received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie SkłodowskaCurie grant agreement No. 101068688.

What we call urban planning today was once about creating; creating novel urban experiences, new lifestyles, or perhaps completely new cities and neighbourhoods. But even in the peak of its very short-lived popularity, urban planning did not bask in the limelight as a ‘creative’ job, nor did its practitioners pride themselves on their creative prowess! Richard Florida’s (in)famous creative class list included architects but not urban planners and even Charles Landry’s creative city idea did not accord planners a pivotal role in its vision. With creativity’s and urban planning’s appeal themselves waning, phrases such as ‘creative urbanism’, ‘creative urban planning’, or ‘creative urban planner’ have increasingly become a rarity.

Creativity, the word that once oozed positivity, has amassed varied negative connotations today. Some boldly declare their opposition to creativity while others do their best to substitute the word with less tainted terms devoid of unfavourable association. Imagination seems to be a new favourite all-encompassing replacement for words that once referred to thinking differently and doing things differently. Creativity is consigned once again solely to the realm of art. Anyone striving for creativity beyond art is constantly reminded that most probably they are engaging in a form of exploitation veiled under the pretence of intellectual liberty and collective work. The politically correct move for planners today is to keep a prudent distance from this notion altogether.

Urban planning’s struggles with finding its functional niche within the realm of social science, political science and society are not helping the situation either. Once branded as engineering, then framed as a political pursuit, and now appearing more as a symbolic custodian of the common good, planning has always grappled with its identity and power in shaping urban life. This ongoing unease has subtly eroded the confidence of planners in their taking bold actions. So it is no wonder that the combination of the terms, creative and urban planning, have had rare appearances in the planning literature in the past decades and the likelihood of them appearing together is diminishing ever more conspicuously.

Yet, even among the handful of works on creative urban planning, two accounts particularly stand out. One written by a landscape designer, Christopher Tunnard , in 1951, frustrated by the then-diminishing quality of urban life, and one written by an urban scholar, Cecilia Dinardi in 2022, frustrated with the growing number of exploitative creative urban practices. Comparing the content of what they lay out as an alternative would be futile. But they each have elements that illuminate their distinct perspectives on creativity and urban decision-making process, epitomizing the dominant narrative of their time.

We train too many ‘practical’ men – what errors are committed in the name of practicality! – and too few artists.

Tunnard was a well-known landscape designer who gained interest in urban planning matters; partly sparked by the decline in the quality of urban life in American cities during the early 1950s, and partly driven by his background in landscape design and collaborations with urban planners in site regeneration projects. In his 1951 paper, titled ‘creative urbanism’ he unveiled his vision for 20th-century urban planning and its institution.

By the end of the 1940s, cities were becoming bigger and more diverse, and the works of planners were becoming increasingly complex. New institutions emerged, grappling with urban complexity. Yet, Tunnard discerned a flaw in their design; planning institutions tried to take responsibility for a variety of tasks, they were too vague in defining their role and most important of all, their design did not lend creative autonomy to those working within them.

His suggestion was to redefine urban planning's overall goal, carefully identify the tasks that are needed to achieve that goal, outline what skills are needed to fulfil those tasks and design educational courses to train future generations of urban planners accordingly. To him what mattered was the totality of the process for managing urban areas rather than defining and making a case for a new profession, called urban planning.

This situation accounts for the varied definitions of the planner’s function which are current and the pretensions of many ‘planners’ to assume powers that they might more modestly disown. It may be asked whether or not in a democratic society either the private owner or the proper branch of government acting for the people, as the case may be, can still be the originator and controller of the program for planning. If the answer is ‘yes’ (‘no’ would surely be an invidious claim on the part of the planner) then the sandwich should be inspected for possible extraneous matter in the filling. It is likely that as a result of this inspection, most functions exceeding the powers of research and interpretation of research or recommendation could be removed.

What he proposed was uniquely a designer's take on the totality of urban planning processes. While his words often seem to advocate for making the city beautiful and aesthetically pleasing, his true preoccupation was with the ‘experience’ of the residents in cities and urban planners in their institutions. As a designer, he very well knew that clarity of role translates to well-defined responsibilities and consequently more creative agency. For him in essence planning and managing urban areas were creative endeavours which in the then-emerging institutions were being reduced to analytical and administrative tasks.

Interestingly, he also underscored the significance of terminologies used in referring to tasks included in urban management and planning. He gave a very insightful history of why urban planning was once called civic design, technocrats, and later planners and how this change in terminologies used reflected the changing planners’ tasks and goals. Throughout his writing, he uses adjectives to better define the specific type of planner that he is referring to; real planner, manager, visual planner, civic designer, administrative planner, etc. The terminology he used in describing his creative urbanism vision, is similar to what product designers use today in describing their processes and roles. He calls the outcome of creative urbanism, the product of creative design, and the person calling for a new initiative, a product owner

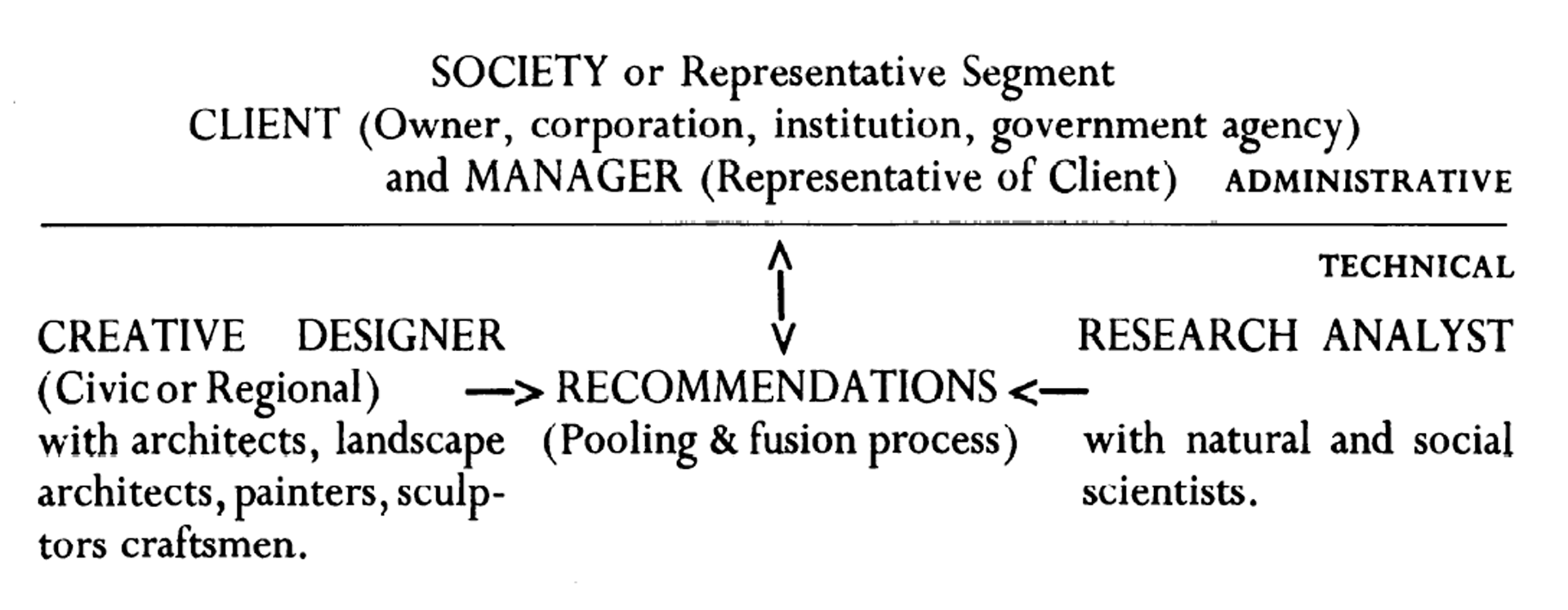

His suggested approach and tasks were this:

Such an institution design, to him, “would make clear-cut the role of the civic designer, restoring some of his early powers and reducing those of the socio-technical scientist. It would also prevent the assumption of specialised research powers by the civic design who is very rarely qualified to undertake them. ” For Tunnard, it was crucial that the creative tasks won’t be limited by structures and frames. Like many other designers, he believed that one cannot imagine, create or think differently once they are bound to work within frames:

We train too many ‘practical’ men – what errors are committed in the name of practicality! – and too few artists. Divorce sculpture, painting and – unthinkable but true, even architecture from city planning – reduce it to a practical working out of traffic flow and correct land use, and what is left? Not a city, surely. The city is supposed to rise upon this base, but it will be an unimaginative thing, a perpetuation past errors in modern form.

Tunnard starting from the totality of urban planners’ experience also meant that he could discuss what tools and technologies each actor might find more helpful to use. He could also define the nature of collaborations between various actors and the expected outcomes from such collaborations.

Tunnard’s work, despite its depth, is, for the most part, ignored in the field of planning. I have to admit that if it was not for the sake of research on creative urbanism I would have not come across his work. Much of what my generation of planning students know about creative urbanism is through the work of Charles Landry, David Yencken and Richard Florida; all encapsulated in what is known as ‘creative economy’. For us, creativity is either exclusively related to works of art or portrayed as a commodity and necessary resource in the economy that had shifted from material resources to intangible assets like data and novel ideas. The institutions these works presented for creative urbanism were completely different from what early designers like Tunnard had in mind. The main aim is not only to maximize the benefits of the new ideas but also to make the creation of new ideas easier, cheaper and more sustainable. Popularizing the idea that everyone can think creatively and come up with new ideas hence seems a logical strategy.

The proliferation of frameworks and support systems gave this illusion that by following certain steps anyone regardless of their cognitive skills and professional background can come up with new ideas. The more people could provide new ideas cheaply and more effectively, the bigger and faster the economy could grow. The work of Dinardi, although criticizing the exploitations happening in these practices, is aligned with the core idea of the creative economy, in assuming creativity as a valuable asset. She writes:

The creativity underpinning this type of urban planning has a variety of sources – from the activities shaping and revitalising urban space, to the process of design and implementation, and the ways in which social groups are included in the process. The focus is on both top-down and bottom-up practices – on the one hand, official governmental policies for culture-led urban regeneration and creative industry-based strategies, such as creative hubs or incubators for small and medium creative enterprises; on the other, grassroots-led projects using culture and the arts for urban transformation.

Similar to many other social scientists and urban thinkers of her time, Dinardi calls for these processes to become more inclusive, geared towards common goals, particularly sustainability, and more towards sharing the profit rather than making the profit exclusive to certain groups. The critiques of creativity narratives inspired by the creative economy, neither criticize the idea of creativity as something accessible to everyone nor are against the idea of value creation from creativity. What they argue is for these practices to be fairer and more geared towards the common good.

Involving more and more people in decision-making is also aligned with the democratic urge for inclusion and openness, particularly where decision-making is becoming increasingly exclusive and filled with technical jargon. Collaborative processes, innovation helix models, and public participatory methods were then the killing of two birds with one stone for the creative economy proponents. But, the more collaborative these decision-making and visioning practices become, the roles and responsibilities become more fluid, and ultimately all actors involved have less creative autonomy.

Engaging in vagueness is embraced as agility and increased variety of ideas as inclusiveness. The attempts to define the role of the planner in such processes often portray the planner as a mediator, facilitator or enabler. Recent reviews of creative practices resulting from urban living labs concluded that the municipality’s and planner’s roles are often reduced to the communicator, enabler or mediator between actors. Planners neither call the shots nor take final decisions in such practices.

If Tunnard was presented with the current model, he would have argued that the creative autonomy of all those involved in the process of management and planning of urban areas is becoming increasingly diminished. While to a 21st-century planner, embracing the chaotic nature of decision-making itself is perceived as an achievement in letting go of control over urban processes. After all, planning theorists have spent the past decades arguing for planning as a political vocation, and have experimented with all sorts of settings to distance themselves from the image of planners as technocrats obsessed with control and power.

Creative urban planning today is no longer about those creative individuals with the right training and cognitive skills experiencing communities and digesting information to come up with new ideas. Creative urban planning today relies on collective eureka moments, chances, and sudden sparks. Yet, tries its best to engineer these moments. It looks more at an idea rather than its implementation. For a sense of agency, and inclusiveness rather than its realization per se.

It is no surprise then that education programs of planning find it hard to keep up with the current models. The role of planners and their contribution to these processes is vaguer than ever. it is not clear what skills planning students need to obtain to reach their goals in these processes, it is not clear what their goals are in these processes either. The education of planning inevitably remains rooted in rational and technocratic ideas of planning, not because it is favoured over current models but because it is easier to make into a system, evaluate, and demonstrate its impact. After all, in current models, expertise is somehow portrayed as more of an obstacle than an opportunity for coming up with new ideas. Hence the planning and its role is pushed back to the background to allow for ‘better’ and ‘different’ ideas to surface.

Depending on what narrative of creativity you believe in, you would go for one narrative over the other. There is a wide range of arguments pro and against each narrative. But an important thing is to engage with questions about what role creativity plays in urban planning. To not be afraid of questioning the value of such collective-oriented forms of creativity and to respect individuality and the creative autonomy of all involved in creative urban planning practices without the fear of promoting non-democratic values.